Symptom as Message

Many people seek therapy because their day-to-day life has become disrupted by a symptom.

The symptoms therapists work with, however, are not medical in nature. This is why therapists do not require medical training.

Rather than evidence of an illness or biochemical imbalance, therapists see a symptom as a message—a way of letting ourselves know we are somehow out of sync with life or ourselves.

A symptom, in therapy, is a meaningful response to life’s difficulties.

Interpreting a Symptom: Medicine and Therapy

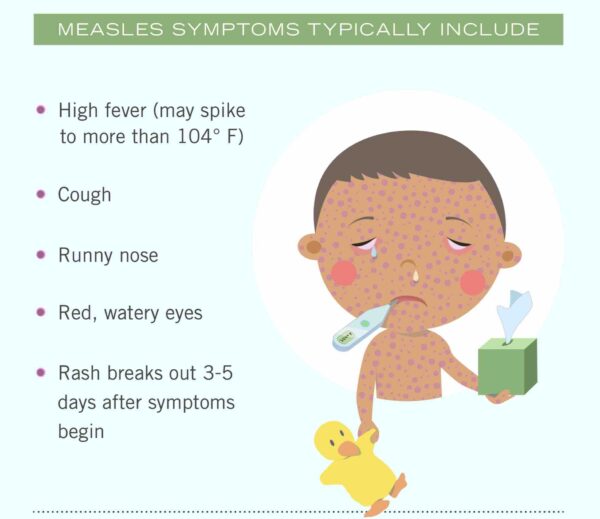

We recognise medical symptoms—visible signs like rashes or fevers that point to physical illness.

Measles, for instance, announces itself through fever, cough, and rash—a clear causal chain.

Medicine treats the underlying condition, not the symptom.

Therapy addresses another class of symptom altogether—not of disease, but of psychological processes like repression.

Symptom as Substitute

Repression—along with disavowal and foreclosure—is one the basic ideas of therapy. It operates beyond awareness, removing unacceptable thoughts, memories, or satisfactions from consciousness and replacing them with disguised substitutes.

A symptom, then, can signal repression’s work: a distorted stand-in for what could not be admitted.

Everyday behaviours often reveal this process. Take someone who prefaces a remark with ‘I don’t wish to criticise you, but…’. Their unsolicited denial may be symptomatic of repression—simultaneously denying and betraying what they cannot admit.

Unlike medical symptoms, therapy’s symptoms are protective formations. They tell us we’ve fallen out of sync with ourselves.

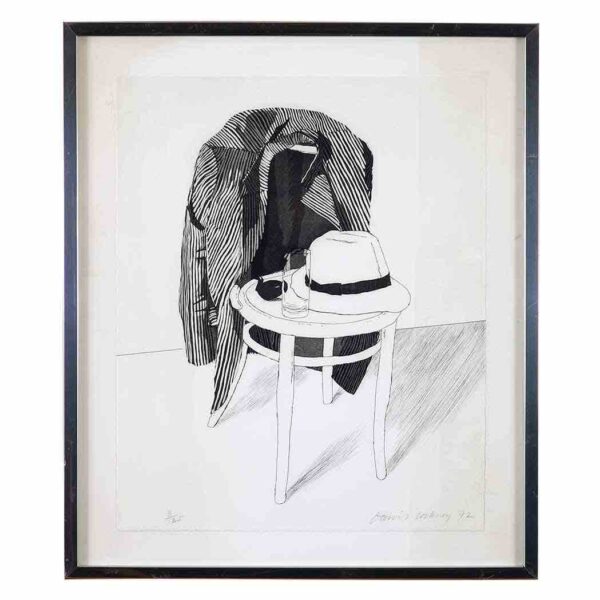

A Portrait with the Subject Missing

An artwork by British artist David Hockney provides a way to deepen our understanding of therapy symptoms.

David Hockney

Panama Hat from Prints for Phoenix House, 1972

Etching and acquaint, 43x34cm

Edition of 125, © David Hockney

Hockney’s Panama Hat emerged from a conversation between Hockney and his friend Henry Geldzahler, who was fundraising for the charity Phoenix House. Geldzahler recalls:

Hockney said, “Let me do a portrait of you” and I said “You really can’t because I am fund-raising for them. It would look a little funny.” So Hockney said, “Well”, and just sat down… and in about an hour, he did my jacket, my hat, my pipe and my iced coffee. I like that picture because it’s a portrait of a subject with the subject missing.

The result—a disguised substitute for what could not be represented directly—echoes how symptoms function in therapy.

Symptom and Nonsense

That repression involves substitution explains another feature of therapy symptoms: their apparent nonsense.

Some feel compelled to check a door lock not once or twice, but repeatedly. Others erupt over seeming trivialities.

That these behaviours seem nonsensical—irrational—is the inevitable consequence of repression: the real subject is missing or disguised.

Symptom as Message

Repression enables everyday life to proceed by providing disguised substitutes for what cannot be admitted.

Symptoms, in this sense, render the everyday ordinary—routine, matter-of-fact, even second nature.

It is when repression falters that people may turn to therapy—not because they have a symptom, but because maintaining it has grown too disruptive or costly.

Indeed, after starting therapy, some are surprised to trace their symptom back to earlier moments—or entire chapters—of life.

Symptom and the Question of Style

The first task of therapy is not to eliminate the symptom, but to approach it as a compromise or protective formation: something half-expressed, deeply personal, and particular to you.

But not all symptoms are the consequence of negation through repression, which I’ve considered here. Some clients negate by other means — disavowal or foreclosure — and others present with symptoms where negation plays little or no part, as in the case of trauma-related symptoms.

What unites the symptoms therapists encounter, however, is that they are messages — each speaking in its own way, according to its own dialect and style.

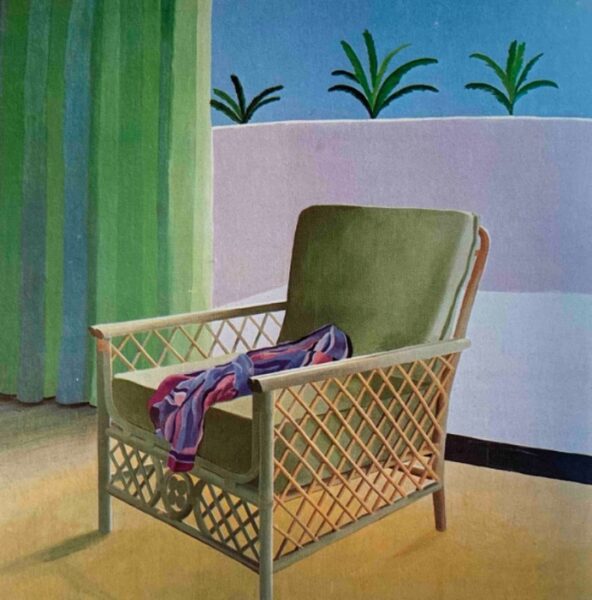

A Final Question

To close, let’s turn to another work by Hockney, his 1972 painting Chair and Shirt.

At first glance, the work appears to be a straightforward still-life. However, once we register its size — 183 x 183 cm (6ft x 6ft) — the almost monumental scale seems at odds with the subject’s apparent simplicity.

If the dimensions render the painting enigmatic, might the ‘substitution’ characteristic of the earlier print, Panama Hat, have been carried across to this work? And if so, what might the missing or disguised subject of this painting be?

David Hockney, Chair and Shirt, 1972

Acrylic paint on canvas, 183x183cm

Private collection © David Hockney

Notes

The measles infographic is taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (accessed June 2019)

https://www.cdc.gov/measles/parent-infographic.html

Some behavioural therapies—CBT, for example—focus on symptom management without exploring underlying causes. For more on this distinction, see our blog on phobias.

Henry Geldzahler recalls his conversation with Hockney in the periodical Art in America, February 1981.

For further reading on Hockney’s use of displacement or metonymy, see chapter four of the book I co-authored with Dr Ulrich Luckhardt, David Hockney Paintings, Prestel 1994.