Depression, Mourning and Melancholia

An Explosion of Depression?

Google’s release in 2017 of the UK’s popular search terms led ITV News to claim, ‘Britain amongst the most depressed and anxious countries in the world.’

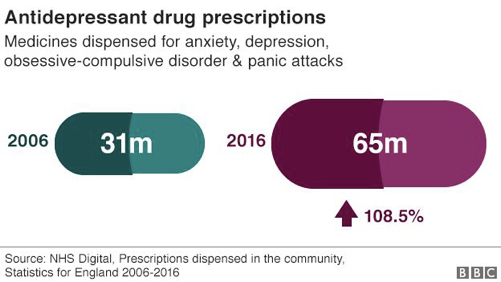

In an article based on figures from NHS Digital, also released in 2017, BBC News reported anti-depressants to be the most common treatment for depression and published a chart showing prescriptions have more than doubled in the last ten years.

However, for therapists there is no single depression as these news headlines may suggest.

Therapy involves going beyond this catch-all idea

Therapy involves going beyond this catch-all idea in order to come to terms with the ways in which we respond to difficult experiences of being in the world.

What is Depression?

I invite clients to begin describing what ‘depressed’ or ‘depression’ means for them, recognising that speaking about difficult subjects may not be easy.

As clients begin to talk, however, an individual life of complexity comes into view from behind this catch-all term.

For some clients, depression describes a feeling of discontent with society, a resignation and withdrawal, even isolation.

For others, it describes powerful feelings of despair, grief, being disconsolate and mournful.

Depression can mean the loss of a sense of self, an experience of emptiness, or of a void that threatens to engulf.

Depression might be marked by disgust with oneself, and a relentless self-criticism.

Depression can describe anxious, fearful and guilty states along with emotional flatness or blankness.

As clients talk, it becomes apparent that depression can be frequent, persistent or intermittent.

It might be associated with a separation from, or loss of a person, relationship, career, or something less tangible or apparent: the loss of a belief, an ideal or a faith.

As this brief description may suggest, the idea of a single and uniform depression implied by news headlines is probably misleading.

We can explore this further by focusing on a couple of examples involving separation and loss.

Our Identity

Some of our strongest emotional ties come about from our identifying with a person, object, situation, environment or belief.

Identification results in a sense of self

Identification is powerful because it results in a sense of self, of who or what we are.

Advertisers understand this process very well.

What often makes an advertising campaign successful is the degree to which it leads us to recognise ourselves in the product being advertised.

We identify ourselves as a Caffe Nero and not a Starbucks person, a Persil and not an Ariel person, a Tesco and not a Sainsbury person, etc.

Mourning

When we experience a loss, we loose an identification, a sense of who or what we are.

Grief is our response, and mourning is the unsettling and often painful time of working things through.

Mourning requires other people with whom we can acknowledge and memorialise our loss.

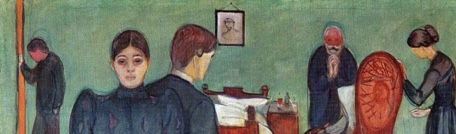

Munch, Death in the Sickroom, 1893

In his 1893 painting Death in the Sickroom, the Norwegian artist, Edvard Munch, seems to point to the social as well as the individual nature of mourning.

A death has just occurred, and family members seem isolated. They are shown turned away from one another and eye contact is avoided.

A connection between them is nevertheless acknowledged by their mirroring and echoing one another through bodily posture and gesture.

For example, notice how the posture of the figure on the left is repeated by the figure on the right.

However, it may be that there is no one to support our mourning, or that asking for support is not possible since we have to be ‘the strong one.’

Mourning can then become protracted, and the depressed feelings in our grief may become too much.

Working with a therapist can reduce the impact by allowing us to mourn.

Melancholy

Some people describe depressed feelings that are long standing and for which it is difficult to attribute a cause.

It is as if a shadow had fallen over them, as though the sun had become eclipsed. Another picture can help us explore this.

Durer, Melancholia, 1514

Melancholia is a 1514 art work by the German Renaissance artist, Albrecht Durer. The title and date appear within the work itself.

In the foreground is the winged figure of Melancholia, hemmed in and with darkened face.

The various elements in the picture reference the depressed feelings not of mourning but of melancholy, the most conspicuous being:

• The dog, a symbol in Western art of our identification with others, is shown shrivelled, half-starved and with eyes closed. Winston Churchill referred to his depression as his ‘black dog’.

• The tools of craft, art and science are strewn over the floor like rubbish, clearly no longer of significance or value.

• Almost everything in the foreground scene is static, including the scales and bell. Nothing moves except for grains of sand in the hour glass whose chambers are shown with equal amounts of sand.

In Melancholia time passes and nothing happens: the distinction between life and death is blurred.

Some recognise the figure of Melancholia in a song by the English composer John Dowland, In Darkness Let Me Dwell:

Thus, wedded to my woes and bedded to my tomb,

O let me Living die, till death do come.

the distinction between life and death is blurred

Melancholics are unable to separate from that which has been lost – as can happen through mourning – since they have identified with loss itself.

This experience can be painful, invasive, even ravaging.

Working with a therapist can help mediate this, perhaps even enabling the tools of craft, art and science to take on significance again.

Depression and Therapy

We have looked at how depressed feelings form part of two very different processes, mourning and melancholia.

This suggests there is no standard or uniform depression as the news headlines which began this article imply.

Melancholia’s Dog?

The reports of an explosion of depression cover a period when there has also been an escalation in homelessness.

Five-hundred years after Durer’s artwork, is Melancholia’s dog to be found with the homeless and beggars in our towns and cities?

The similarities between Durer’s artwork and news photographs of the homeless certainly invite reflection.

Jon, Homeless Man and his Dog, 2013

Notes to article

The ITV News story is here (accessed 14/05/18),

http://www.itv.com/news/2017-05-10/britain-is-the-seventh-most-depressed-country-in-the-world-search-data-suggests/

The BBC chart is here (accessed 14/05/18),

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-41125009

It is Harrison Birtwistle who references John Dowland’s song (accessed 15/05/18),

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2003/aug/30/art.proms2003

The photograph, ‘Homeless Man and his Dog’ (2013) by Jon, is taken from (accessed 15/05/18, pixelation added),

flickr.com/photos/jb-london/8729276154

The report of an escalation in homelessness is found in The JRF’s Homeless Monitor: England 2018,

https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/homelessness-monitor-england-2018

For further reading on this topic see Darian Leader’s clear and accessible book, The New Black: Mourning, Melancholia and Depression (2008).